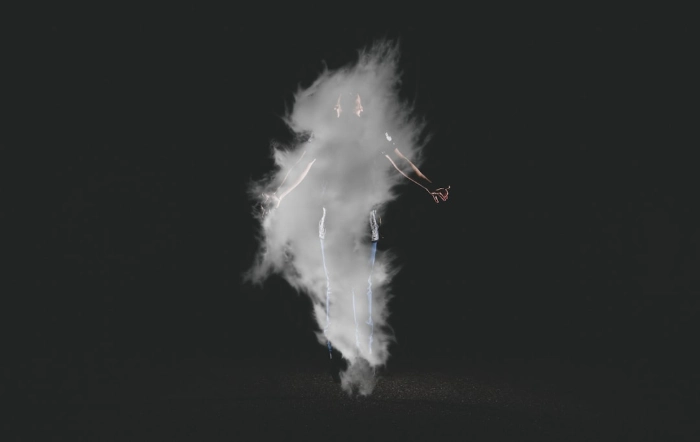

The Miracle of Jesus driving out the evil spirit from a man in Capernaum

The miracle of Jesus driving out an evil spirit from a man in Capernaum (Mark 1:21–28; Luke 4:31–37) is a powerful demonstration of Christ’s sovereign authority and a foretaste of His redemptive work in establishing the Kingdom of God. This miracle emphasizes God’s absolute sovereignty, the total depravity of humanity, and the necessity of divine grace for salvation—all of which are illuminated in this miraculous event.

The event begins with Jesus teaching in the synagogue on the Sabbath, where people are astonished at His authority. Unlike the scribes, Jesus teaches as one who possesses inherent authority. This authority is rooted in His divine nature. Jesus is not merely a prophet or a moral teacher; He is the eternal Son of God (John 1:1,14), through whom and for whom all things were made (Colossians 1:16). His command over the demon is not ritualistic or derivative, but sovereign and immediate—reflecting divine prerogative over all creation, including the spiritual realm.

The demon’s recognition of Jesus—"I know who You are—the Holy One of God!"—reveals a critical theological truth: even the forces of darkness are subject to God’s sovereign will and cannot act apart from His permission (cf. Job 1:12). This aligns with the doctrine of God’s providence, where all events, including the actions of demons, occur under God’s sovereign governance (Westminster Confession of Faith, Chapter 5). The demon’s fear—“Have you come to destroy us?”—testifies to Christ’s eschatological mission to overthrow the kingdom of darkness and establish His rule of righteousness.

This exorcism also reflects the total depravity of man and the need for divine intervention. The possessed man represents humanity’s bondage to sin and Satan (Ephesians 2:1–3). Humanity is incapable of freeing itself from this condition. Just as the man in Capernaum could not expel the demon by his own will or strength, so too are sinners helpless apart from the regenerating work of the Holy Spirit. Christ’s command—“Be silent, and come out of him!”—is a picture of sovereign grace. It is God who acts first, effecting liberation. This is monergism: the belief that salvation is the work of God alone.

Furthermore, this miracle anticipates the cosmic scope of Christ’s redemptive work. The coming of the Kingdom of God entails not only personal salvation but also the defeat of all powers opposed to God’s rule. Christ’s exorcisms serve as signs of His triumph over Satan, a triumph completed at the cross (Colossians 2:15) and consummated at His return. Reformed eschatology sees this as the already-but-not-yet dynamic of the Kingdom: Jesus has inaugurated His reign, but its fullness awaits the final judgment.

In conclusion, the exorcism in Capernaum is not merely a display of compassion or power—it is a revelation of Christ’s sovereign authority, the radical nature of human bondage, and the necessity of divine grace. It is a glimpse of the redemptive reign of Christ, in which sinners are delivered from darkness and brought into the marvelous light of God’s Kingdom.